Whether you’re prepping for your civil-procedure exam or studying for the bar exam, you’ll want to understand how amendments to pleadings can relate back to the original pleading date. It’s like time travel for parties and lawyers. Let’s take a closer look at this useful—and testable—part of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.

Why Do We Need Relation Back?

Pleadings, such as the complaint and the answer, are the foundation of any civil lawsuit.

But parties don’t always get the pleadings right the first time. A pleading might accidentally leave out a party or a claim. Sometimes, discovery will reveal new information that a party didn’t have when it filed its original pleadings. A plaintiff might sue the wrong defendant or the right defendant under the wrong name. Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 15 allows the parties to amend their pleadings for these and other reasons.

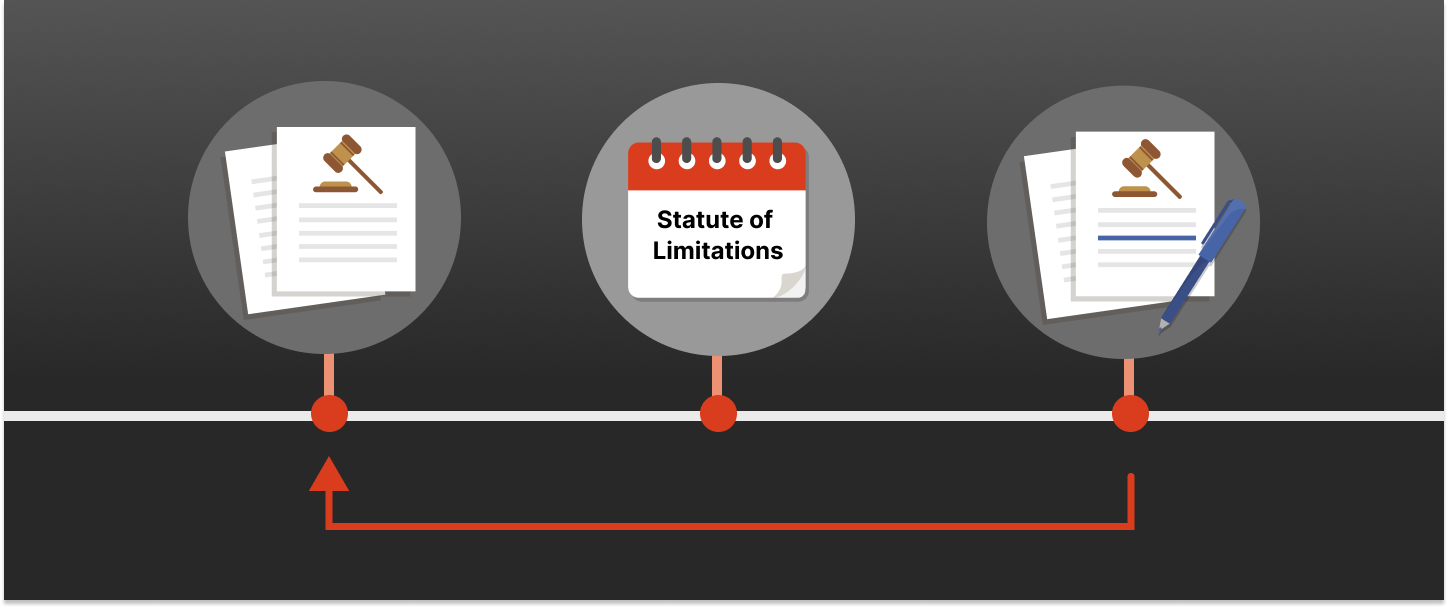

Rule 15 also allows certain amendments to relate back to the original pleading date. Relation back means that an amendment counts chronologically as if it were part of the original pleading. Thus, relation back enables parties to incorporate new information or fix previous errors or omissions without suffering a time-based penalty such as the statute of limitations.

But parties don’t always get the pleadings right the first time. A pleading might accidentally leave out a party or a claim. Sometimes, discovery will reveal new information that a party didn’t have when it filed its original pleadings. A plaintiff might sue the wrong defendant or the right defendant under the wrong name. Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 15 allows the parties to amend their pleadings for these and other reasons.

Rule 15 also allows certain amendments to relate back to the original pleading date. Relation back means that an amendment counts chronologically as if it were part of the original pleading. Thus, relation back enables parties to incorporate new information or fix previous errors or omissions without suffering a time-based penalty such as the statute of limitations.

Three Ways to Relate Back

One helpful thing about relation back is that there are only 3 ways to do it, and they’re all fairly logical.

In plain English, relation back is allowed (1) if the law that provides the statute of limitations permits relation back; (2) if the amendment involves the same events as the original pleading; and (3) in certain situations, if the amendment changes a defending party or a defending party’s name.

Let’s consider each of these in more detail.

In plain English, relation back is allowed (1) if the law that provides the statute of limitations permits relation back; (2) if the amendment involves the same events as the original pleading; and (3) in certain situations, if the amendment changes a defending party or a defending party’s name.

Let’s consider each of these in more detail.

Rule 15(c)(1)(A): The law that provides the statute of limitations

Rule 15(c)(1)(A) permits relation back if the law that creates the applicable statute of limitations allows it. This form of relation back enables the federal courts to incorporate state-law relation-back rules in diversity cases.

For example, let’s say an anonymous blogger published an article that accused a politician of stealing campaign funds to gamble on horse races. The politician lived in State A. The politician knew that the blog was based in State B, but he didn’t know exactly who ran the blog or who wrote the article.

State A law provided a 2-year statute of limitations for defamation. But State A law also had a so-called John Doe provision, which tolled the statute of limitations as to unknown defendants if a complaint was filed and allowed relation back once a plaintiff could finally identify an unknown defendant.

One month before the statute of limitations expired, the politician filed a federal-diversity case against John Doe, alleging defamation under State A law. Two months later, the politician discovered that the blog was run by a corporation called XPose, Inc. The politician sought to amend his complaint to name XPose, Inc. as the defendant.

In this example, the applicable state law incorporates the John Doe tolling provision, which expressly allows relation back if a plaintiff seeks to substitute a named defendant for a John Doe defendant. Therefore, under Rule 15(c)(1)(A), the politician’s amendment will relate back to the date of the original complaint, one month before the statute of limitations expired. XPose, Inc. therefore will not have a statute-of-limitations defense.

For example, let’s say an anonymous blogger published an article that accused a politician of stealing campaign funds to gamble on horse races. The politician lived in State A. The politician knew that the blog was based in State B, but he didn’t know exactly who ran the blog or who wrote the article.

State A law provided a 2-year statute of limitations for defamation. But State A law also had a so-called John Doe provision, which tolled the statute of limitations as to unknown defendants if a complaint was filed and allowed relation back once a plaintiff could finally identify an unknown defendant.

One month before the statute of limitations expired, the politician filed a federal-diversity case against John Doe, alleging defamation under State A law. Two months later, the politician discovered that the blog was run by a corporation called XPose, Inc. The politician sought to amend his complaint to name XPose, Inc. as the defendant.

In this example, the applicable state law incorporates the John Doe tolling provision, which expressly allows relation back if a plaintiff seeks to substitute a named defendant for a John Doe defendant. Therefore, under Rule 15(c)(1)(A), the politician’s amendment will relate back to the date of the original complaint, one month before the statute of limitations expired. XPose, Inc. therefore will not have a statute-of-limitations defense.

Rule 15(c)(1)(B): The same conduct, transaction, or occurrence

Rule 15(c)(1)(B) allows relation back if the amendment asserts a claim or defense that arose out of the conduct, transaction, or occurrence set out—or attempted to be set out—in the original pleading.

For example, let’s say the politician’s original complaint correctly named XPose, Inc. as the defendant. The complaint alleged defamation. But the politician’s lawyer carelessly failed to include a second claim for intentional infliction of emotional distress (IIED) based on the same publication. The statute of limitations for IIED expired one week after the politician filed the complaint.

Three months later, the politician hired a new lawyer who sought to amend the complaint to add the IIED claim. XPose, Inc. contended that the IIED claim was barred by the statute of limitations.

But the politician’s claim can be saved by Rule 15(c)(1)(B). The IIED claim arose from the same publication as the defamation claim. Therefore, the IIED claim arose from the same transaction or occurrence identified in the original complaint. Consequently, the amendment will relate back to the original pleading’s date, and the IIED claim will be timely.

For example, let’s say the politician’s original complaint correctly named XPose, Inc. as the defendant. The complaint alleged defamation. But the politician’s lawyer carelessly failed to include a second claim for intentional infliction of emotional distress (IIED) based on the same publication. The statute of limitations for IIED expired one week after the politician filed the complaint.

Three months later, the politician hired a new lawyer who sought to amend the complaint to add the IIED claim. XPose, Inc. contended that the IIED claim was barred by the statute of limitations.

But the politician’s claim can be saved by Rule 15(c)(1)(B). The IIED claim arose from the same publication as the defamation claim. Therefore, the IIED claim arose from the same transaction or occurrence identified in the original complaint. Consequently, the amendment will relate back to the original pleading’s date, and the IIED claim will be timely.

Rule 15(c)(1)(C): Changing a party or the naming of a party

Rule 15(c)(1)(C) describes the most intricate relation-back scenario, but it’s not too difficult once you understand what the rule does.

Let’s say the politician originally sued XPose, Inc. for defamation and IIED one week before the statute of limitations expired on both claims. However, the politician’s lawyer made a different mistake, this time by misnaming the defendant. The blog was actually run by a company called XPose, Ltd., and there was no such entity as XPose, Inc.

The politician’s lawyer timely served the summons and complaint on an individual named Jan Smith, whom the lawyer believed to be the president of XPose, Inc. Smith was, in fact, the president of XPose, Ltd. Smith accepted service but didn’t say anything about the improper naming.

Three months later, the politician’s lawyer learned that the correct defendant was XPose, Ltd. The statute of limitations had expired. What can the lawyer do?

This time, the lawyer can seek to amend the complaint to correctly name the defendant. That amendment can relate back to the original pleading date under Rule 15(c)(1)(C). The rule’s language is a bit convoluted, but the concept is straightforward. An amendment can relate back to the original pleading date if it changes the party or the naming of a party against whom a claim is asserted and if a few additional conditions are satisfied.

First, the amendment must satisfy Rule 15(c)(1)(B) by asserting a claim that arises from the same conduct, transaction, or occurrence as the original pleading. Here, the amended complaint seeks to assert the same claims as the original complaint, only against a different defendant. The first condition is therefore satisfied.

Second, within the time allowed for serving the original summons and complaint, the new (or newly named) party must have received sufficient notice of the case so as not to be prejudiced in defending it. Here, the politician served Jan Smith within the time allowed for serving the original summons and complaint. Through Smith, XPose, Ltd. received notice of the case within the initial service period. Thus, XPose, Ltd. won’t be prejudiced by the amendment.

Third, within the time allowed for serving the original summons and complaint, the new (or newly named) party either knew or should have known that the party would’ve been sued originally but for a mistake about the proper party’s identity. Here, Smith, on behalf of XPose, Ltd., surely knew or should’ve known that naming XPose, Inc. was a mistake and that the correct defendant was XPose, Ltd.

The amendment changing the defendant’s name from XPose, Inc. to XPose, Ltd. satisfies all the conditions required for relation back. Therefore, the amendment relates back to the original pleading date, before the statute of limitations expired. And the politician’s lawyer can breathe a sigh of relief.

We can summarize Rule 15(c)(1)(C) in a more compact form. An amendment relates back if:

Let’s say the politician originally sued XPose, Inc. for defamation and IIED one week before the statute of limitations expired on both claims. However, the politician’s lawyer made a different mistake, this time by misnaming the defendant. The blog was actually run by a company called XPose, Ltd., and there was no such entity as XPose, Inc.

The politician’s lawyer timely served the summons and complaint on an individual named Jan Smith, whom the lawyer believed to be the president of XPose, Inc. Smith was, in fact, the president of XPose, Ltd. Smith accepted service but didn’t say anything about the improper naming.

Three months later, the politician’s lawyer learned that the correct defendant was XPose, Ltd. The statute of limitations had expired. What can the lawyer do?

This time, the lawyer can seek to amend the complaint to correctly name the defendant. That amendment can relate back to the original pleading date under Rule 15(c)(1)(C). The rule’s language is a bit convoluted, but the concept is straightforward. An amendment can relate back to the original pleading date if it changes the party or the naming of a party against whom a claim is asserted and if a few additional conditions are satisfied.

First, the amendment must satisfy Rule 15(c)(1)(B) by asserting a claim that arises from the same conduct, transaction, or occurrence as the original pleading. Here, the amended complaint seeks to assert the same claims as the original complaint, only against a different defendant. The first condition is therefore satisfied.

Second, within the time allowed for serving the original summons and complaint, the new (or newly named) party must have received sufficient notice of the case so as not to be prejudiced in defending it. Here, the politician served Jan Smith within the time allowed for serving the original summons and complaint. Through Smith, XPose, Ltd. received notice of the case within the initial service period. Thus, XPose, Ltd. won’t be prejudiced by the amendment.

Third, within the time allowed for serving the original summons and complaint, the new (or newly named) party either knew or should have known that the party would’ve been sued originally but for a mistake about the proper party’s identity. Here, Smith, on behalf of XPose, Ltd., surely knew or should’ve known that naming XPose, Inc. was a mistake and that the correct defendant was XPose, Ltd.

The amendment changing the defendant’s name from XPose, Inc. to XPose, Ltd. satisfies all the conditions required for relation back. Therefore, the amendment relates back to the original pleading date, before the statute of limitations expired. And the politician’s lawyer can breathe a sigh of relief.

We can summarize Rule 15(c)(1)(C) in a more compact form. An amendment relates back if:

- it changes the defending party or the defending party’s name;

- it arises from the same conduct, transaction, or occurrence as the original pleading; and

- within the time allowed for serving the original summons and complaint, the new party

- received notice of the case such that the party won’t be prejudiced by having to defend it and

- knew or should’ve known that it would’ve been an original party but for mistaken identity.

Final Thoughts

We can see from these examples that relation back is a fairly forgiving process. That’s consistent with the overall approach to amendments under the federal rules. You might recall that courts are supposed to freely grant leave to amend if justice requires. That freedom is consistent with the multiple ways in which amendments can relate back to fix mistakes, accommodate new information, and accomplish justice.

From your first day of law school to your final day of practice, Quimbee is here to help you succeed. Get up to speed on relation back and other civil-procedure concepts with essential video lessons, essay practice exams, and multiple-choice questions. Check out Quimbee Bar Review+ to explore the features students across the country rely on to help them pass the bar exam on their first attempt. To learn more, book a free, 30-minute course tour with a bar review director.

From your first day of law school to your final day of practice, Quimbee is here to help you succeed. Get up to speed on relation back and other civil-procedure concepts with essential video lessons, essay practice exams, and multiple-choice questions. Check out Quimbee Bar Review+ to explore the features students across the country rely on to help them pass the bar exam on their first attempt. To learn more, book a free, 30-minute course tour with a bar review director.

(3).png)