E.C. Styberg Engineering Co. v. Eaton Corp.

United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit

492 F.3d 912 (2007)

- Written by Craig Conway, LLM

Facts

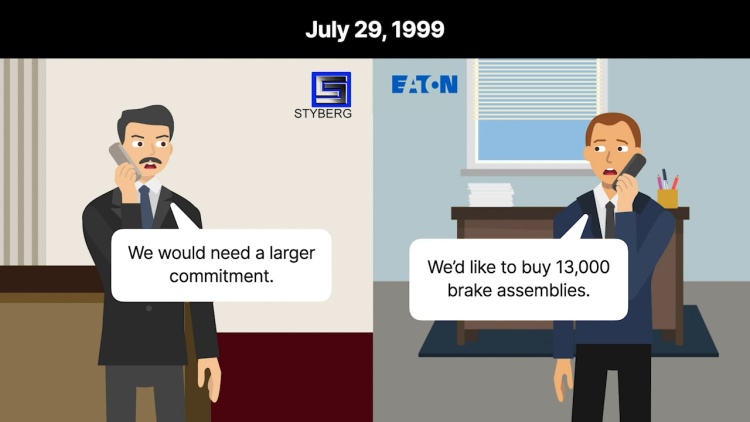

From 1998 to 2000, E.C. Styberg Engineering Company (Styberg) (plaintiff) manufactured a custom brake assembly part for inclusion in Eaton Corporation’s (Eaton) (defendant) six-speed transmission motor vehicle part. In 1999, the parties began negotiating an agreement under which Styberg would produce large quantities of the part for Eaton. During this time several e-mail exchanges and telephone calls between employees of both parties occurred that discussed quantity and price. Lisa Fletcher, an Eaton employee, sent a letter to a Styberg engineer committing Eaton to purchase 13,000 parts. However, Styberg wanted a larger purchase commitment from Eaton to offset its capital investment in manufacturing the parts. Thereafter, no purchase order was ever issued by Eaton for the 13,000 parts. Styberg filed suit against Eaton in district court for breach of contract and sought approximately $3.4 million in damages. After a four-day bench trial, the court held that no contract had existed because the parties had failed to agree on terms. There, the court characterized the various discussions by e-mail, telephone, and letter as evidence of continued negotiations that did not constitute the basis of a formed contract. Styberg appealed.

Rule of Law

Issue

Holding and Reasoning (Flaum, J.)

What to do next…

Here's why 907,000 law students have relied on our case briefs:

- Written by law professors and practitioners, not other law students. 47,100 briefs, keyed to 996 casebooks. Top-notch customer support.

- The right amount of information, includes the facts, issues, rule of law, holding and reasoning, and any concurrences and dissents.

- Access in your classes, works on your mobile and tablet. Massive library of related video lessons and high quality multiple-choice questions.

- Easy to use, uniform format for every case brief. Written in plain English, not in legalese. Our briefs summarize and simplify; they don’t just repeat the court’s language.