Pliva, Inc. v. Mensing

United States Supreme Court

564 U.S. 604, 131 S. Ct. 2567 (2011)

- Written by Jamie Milne, JD

Facts

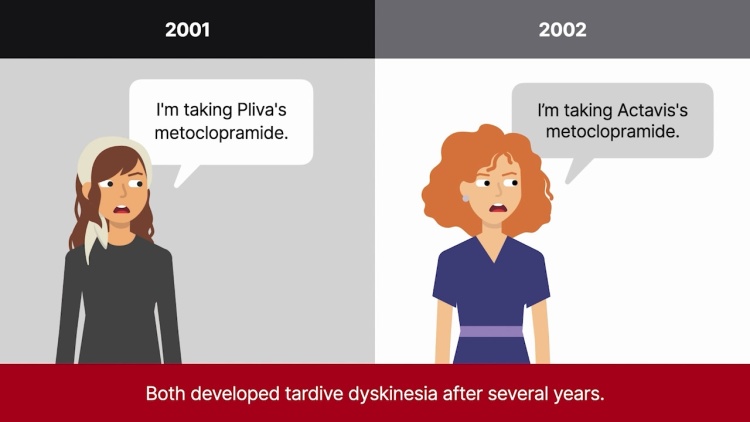

In 1980, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved metoclopramide, sold under the brand name Reglan, to treat digestive problems. Five years later, generic manufacturers (defendants), including Pliva, Inc., began producing generic equivalents. Over time, long-term metoclopramide use was linked with tardive dyskinesia, a severe neurological disorder. As a result, the warning labels on metoclopramide were strengthened multiple times, with the strongest warning adopted in 2009. In 2001 and 2002, Gladys Mensing and Julie Demahy (plaintiffs) were prescribed Reglan and received generic equivalents. After several years, both developed tardive dyskinesia. Mensing and Demahy separately sued multiple generic manufacturers, claiming that the manufacturers violated state tort law by failing to provide adequate warning labels for their drugs. In both actions, the manufacturers moved to dismiss, arguing that federal law preempted the state tort claims because federal law required generic manufacturers to use the same labels as their brand-name counterparts. The district court in Mensing’s case granted dismissal, but the district court in Demahy’s case did not. On appeal, the Fifth and Eighth Circuits both held that the state tort claims were not preempted by federal law. The United States Supreme Court granted certiorari.

Rule of Law

Issue

Holding and Reasoning (Thomas, J.)

What to do next…

Here's why 907,000 law students have relied on our case briefs:

- Written by law professors and practitioners, not other law students. 47,100 briefs, keyed to 996 casebooks. Top-notch customer support.

- The right amount of information, includes the facts, issues, rule of law, holding and reasoning, and any concurrences and dissents.

- Access in your classes, works on your mobile and tablet. Massive library of related video lessons and high quality multiple-choice questions.

- Easy to use, uniform format for every case brief. Written in plain English, not in legalese. Our briefs summarize and simplify; they don’t just repeat the court’s language.