Porter v. Wertz

New York Supreme Court, Appellate Division, First Department

68 A.D.2d 141, 416 N.Y.S.2d 254 (1979)

- Written by Rocco Sainato, JD

Facts

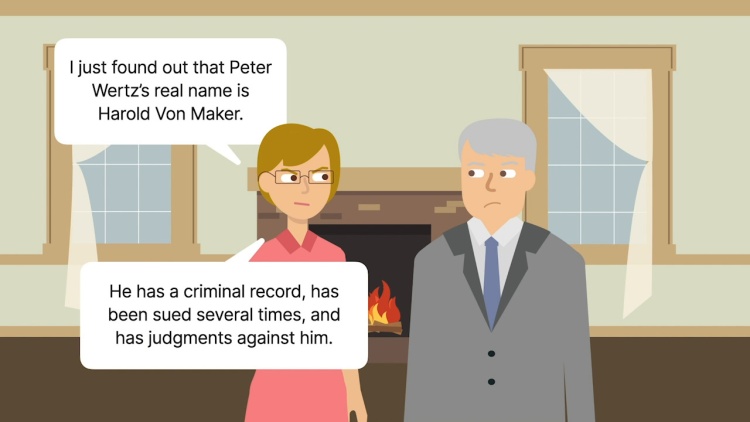

Samuel Porter (plaintiff) owned a painting by the artist Maurice Utrillo. Porter loaned the painting to Harold Von Maker so Von Maker could hang the painting in his home pending his decision on whether or not to purchase it from Porter. Von Maker occasionally used other names, including the name Peter Wertz (defendant). Wertz was a real person who allowed Von Maker to use his name. Von Maker signed an agreement with Porter, stating that the painting would remain Porter’s, and if not returned, $30,000 would be paid to Porter. Von Maker then used the real Peter Wertz to sell the Utrillo painting to Richard Feigen (defendant). Feigen's employee, Mrs. Drew-Bear, then sold the Utrillo painting to another buyer. Neither Feigen nor Drew-Bear made any attempt to determine if Wertz was a reputable art dealer or was authorized to sell the Utrillo. In fact, Wertz was not an art dealer; he worked in a deli. Porter brought an action to recover the painting or its value. After a bench trial, the trial court determined that the affirmative defense of statutory estoppel was inapplicable but that equitable estoppel constituted a bar to Porter’s suit. The court dismissed Porter's complaint, and Porter appealed to the New York Supreme Court Appellate Division, First Department.

Rule of Law

Issue

Holding and Reasoning (Birns, J.)

What to do next…

Here's why 906,000 law students have relied on our case briefs:

- Written by law professors and practitioners, not other law students. 47,100 briefs, keyed to 995 casebooks. Top-notch customer support.

- The right amount of information, includes the facts, issues, rule of law, holding and reasoning, and any concurrences and dissents.

- Access in your classes, works on your mobile and tablet. Massive library of related video lessons and high quality multiple-choice questions.

- Easy to use, uniform format for every case brief. Written in plain English, not in legalese. Our briefs summarize and simplify; they don’t just repeat the court’s language.