Rogers v. Tennessee

United States Supreme Court

532 U.S. 451 (2000)

- Written by Angela Patrick, JD

Facts

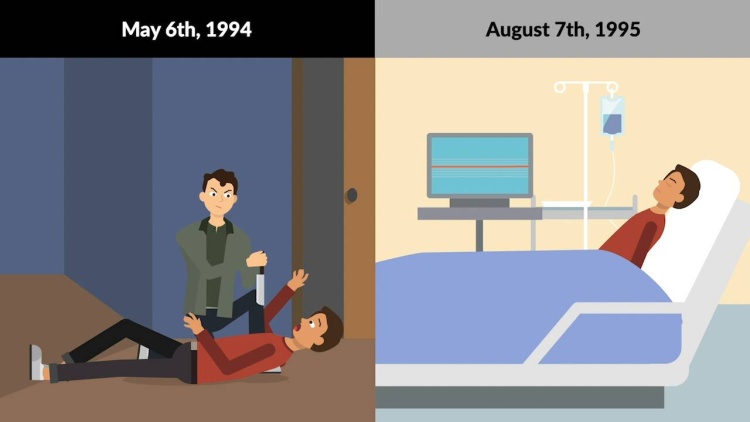

Wilbert Rogers (defendant) stabbed James Bowdery. After surgery, Bowdery slipped into a coma and never recovered. Bowdery died 15 months after Rogers stabbed him. Rogers was convicted of murder pursuant to Tennessee’s criminal-homicide statute. This statute did not mention the year-and-a-day rule, which was a common-law rule that a defendant could not be convicted of murder unless the victim died within a year and a day of the defendant’s act. The rule originated from earlier skepticism about the capabilities of medical science. Three prior published Tennessee cases had mentioned the rule in dicta, but no published Tennessee judicial opinion had ever relied on the rule in a murder case. Rogers appealed, claiming that the year-and-a-day rule prevented his conviction. The Tennessee Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed the conviction. The Tennessee Supreme Court ruled that the year-and-a-day rule had been a part of Tennessee’s common law but that the original reasons for the rule no longer existed. Several other states had abolished the rule by legislation, and most courts that had considered the rule had abolished it. The Tennessee Supreme Court expressly abolished the rule and affirmed Rogers’s conviction. The United States Supreme Court granted certiorari.

Rule of Law

Issue

Holding and Reasoning (O’Connor, J.)

Dissent (Scalia, J.)

What to do next…

Here's why 907,000 law students have relied on our case briefs:

- Written by law professors and practitioners, not other law students. 47,100 briefs, keyed to 996 casebooks. Top-notch customer support.

- The right amount of information, includes the facts, issues, rule of law, holding and reasoning, and any concurrences and dissents.

- Access in your classes, works on your mobile and tablet. Massive library of related video lessons and high quality multiple-choice questions.

- Easy to use, uniform format for every case brief. Written in plain English, not in legalese. Our briefs summarize and simplify; they don’t just repeat the court’s language.