Runyon v. Paley

Supreme Court of North Carolina

416 S.E.2d 177 (1992)

- Written by Patrick Busch, JD

Facts

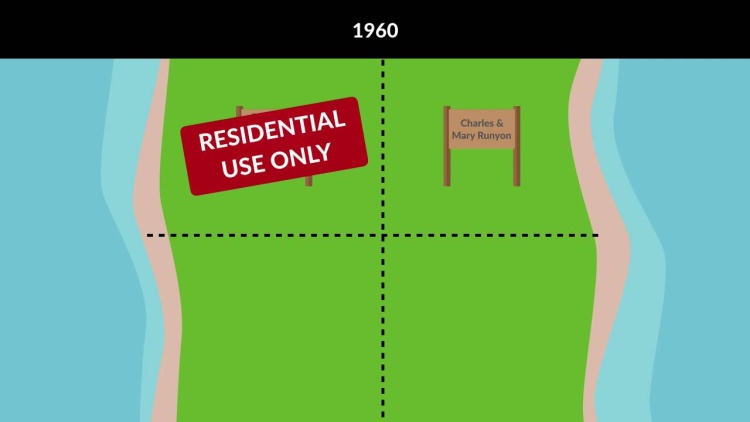

Ruth Bragg Gaskins owned a four-acre tract of land. On May 1, 1954, Gaskins conveyed one and one-half acres of her property to the Runyons (defendants). On January 6, 1960, the Runyons conveyed the land back to Gaskins. Two days later, Gaskins re-conveyed a portion of the one and one-half acre tract in addition to another lot to the Runyons. The next day, on January 9, 1960, Gaskins conveyed the remaining portion of the one and one-half acre tract of land to the Brughs. The deed of conveyance restricted the Brughs from constructing condominiums on the property. The deed indicated that the restrictions would run until they were removed or until nearby properties were put to commercial use. At the time the deed was executed, the Gaskins lived in a residential dwelling located across the street. She lived there until her death in August 1961. After her death, her daughter, Williams (plaintiff), acquired the dwelling. Warren D. Paley (defendant), acquired the Brughs’ property conveyance. Paley then prepared to construct a condominium on the property. Williams brought suit to enjoin Paley from violating the restrictive covenant. The trial court dismissed the case for failure to state a claim. The Court of Appeals affirmed on the grounds that the covenants were personal to Gaskins and unenforceable upon her death.

Rule of Law

Issue

Holding and Reasoning (Meyer, J.)

What to do next…

Here's why 907,000 law students have relied on our case briefs:

- Written by law professors and practitioners, not other law students. 47,100 briefs, keyed to 996 casebooks. Top-notch customer support.

- The right amount of information, includes the facts, issues, rule of law, holding and reasoning, and any concurrences and dissents.

- Access in your classes, works on your mobile and tablet. Massive library of related video lessons and high quality multiple-choice questions.

- Easy to use, uniform format for every case brief. Written in plain English, not in legalese. Our briefs summarize and simplify; they don’t just repeat the court’s language.