Bar Exam Success

Memorization Techniques That Can Help You Succeed on the Bar Exam

Memorization Techniques That Can Help You Succeed on the Bar Exam

Memorization plays a crucial role in success on any closed-book exam, including the bar exam. If you’ve tried cramming, you’ve probably realized that it produces memory that’s here today but gone tomorrow. To remember more from your bar exam course, try memorization techniques that leverage learning science.

To begin, let’s look at how memory works. Our brains process information according to 3 distinct stages.

Seeing and Hearing It—Sensory Memory

Sensory memory is the first stage of information processing. Information from the environment around us enters our sensory memory through 1 of our 5 senses: vision, hearing, smell, taste, or touch. If we pay attention to the information entering our sensory memory, we can shift the information into working memory and create the potential for longer-term storage. But if we leave the information unattended, it doesn’t remain long. Sensory memory lasts milliseconds.

The Brain’s Scratchpad—Working Memory

When we pay attention to information, it enters our working memory, also known as short-term memory. Working memory is the brain’s scratchpad—it’s where we do our conscious cognitive processing, including making decisions and solving problems. Working memory has limited capacity and retains information for a short period of time, about 15–30 seconds. If we want to remember something later, we need to shift it into long-term memory.

The Big Goal—Long-Term Memory

Long-term memory has vast storage capacity and can hold information for days, months, or even years. On an exam, we retrieve information from long-term memory and shift it back to working memory to perform the task required.

Encoding information into long-term memory is essential for success on the bar exam. The essay and multiple-choice portions of the exam test your ability to apply rules to given factual scenarios. You must be able to pull a rule from memory to advance to the next step, applying it to facts. If you cannot recall the rule, you won’t be able to reason to the right result.

You’ll want to recall material as effortlessly as possible. If you must spend mental energy recalling the rule, you won’t be able to devote as much brain space to analyzing the questions and reasoning to an answer.

The bar exam’s expansive coverage places a premium on memorization. Preparing for the Uniform Bar Exam requires mastering 12 areas of law. If you find this prospect daunting, you’re not alone. But with the right memorization techniques, you can commit the material to memory. Let’s explore how to memorize for the bar exam.

Effortful Encoding and Forming Associations

Many students spend the bulk of their bar prep time using passive strategies that take limited mental energy: reading outlines, reviewing notes, or listening to lectures. These “feel-good” strategies produce an illusion of knowing. The rules we hear or see on the page seem familiar, so we think we’ve mastered them. But come exam day, we won’t be able to recall them.

Memorization happens when we put effort into encoding information into our long-term memory. We need to learn rules actively. It’s not enough to receive them passively from an outline or lecture. There are many ways you can employ active learning during bar prep. Try rephrasing a rule in your own words. Teach the rule to someone else. Brainstorm a factual example that fits the rule. Cover the rule up and see whether you can recall it. Take practice questions that test the rule.

Forming associations is also crucial for memorization. If you associate new information with something accessible or meaningful already in your memory, you are better able to recall the new information later. The accessible or meaningful memory serves as a retrieval cue, helping you drag the entire memory back into conscious awareness. Try the following memorization techniques, which use associations to produce a memory-boosting effect.

Mnemonics

Mnemonics are built by associating new information with an accessible mental cue, such as a word or song. Name mnemonics take the first letter of each item in a list to form a word. For example, try memorizing the basics of adverse possession with the mnemonic NACHOS:

- Notorious

- Actual

- Continuous

- Hostile

- Open

- Sole possessor (exclusive)

Acrostic mnemonics use the first letter of each word to form a memorable phrase or sentence. On the bar exam, you’ll need to know the felony-murder rule. Most jurisdictions limit its application to inherently dangerous felonies, crimes that by their nature pose a high risk of injury or death. Use this acrostic mnemonic to memorize the 5 inherently dangerous felonies:

- Ravenous Rob ate Keith’s burger.

- robbery, rape, arson, kidnapping, burglary

Mnemonics come in many forms. Name and acrostic mnemonics use verbal associations. Music mnemonics help you memorize material by setting it to song. The memory-palace method, described below, is a mnemonic that leverages visual and spatial associations.

For best results, try generating mnemonics yourself. The effort used in creating them helps encode information into long-term memory.

Memory Palaces

A memory palace is a place in your mind where you store images. To use this method, you’ll place images along a familiar journey. Associate the concepts you want to remember with landmarks featured on the route. The more familiar the route and the more vivid the associations, the better you’ll remember.

Let’s create a memory palace for venue, a concept frequently tested on the bar exam. The general venue statute contains 3 prongs:

- Venue is proper in a judicial district where any defendant resides, if all defendants reside in the same state.

- Venue is also proper in any district where a substantial part of the events or omissions giving rise to the claim occurred.

- Finally, the statute features a fallback provision. If the first or second statutory methods don’t establish venue, the fallback provision allows venue in any district where the defendant is subject to personal jurisdiction in the case.

Let’s map the venue statute onto your bedroom. We’ll use this route: your bed, a window, and your pajamas.

The statute’s first prong is fundamentally about residence—venue is proper where the defendant resides. To help you memorize, create an association using your bed. Visualize a defendant taking up residence there.

The second prong allows venue where the claim arose. Visualize your bedroom window shattered to create an association with a legal claim.

The final prong is the fallback provision, which allows venue in a district where the defendant is subject to personal jurisdiction. Visualize your pajamas, and associate them with PJ, short for personal jurisdiction. You could even imagine yourself falling backward in your pajamas to remember that personal jurisdiction is the fallback-venue method, applicable only if the first two prongs do not establish a proper venue.

When you want to recall the information, retrace the route through your bedroom. Each stop on the journey—bed, window, pajamas—will help you recall the venue statute.

When you build memory palaces for the bar exam, get creative. You can map rules you need to memorize onto just about anything familiar to you: a route you walk each day, your broom closet, or even your fingers. When you create associations, let your mind go wild. Zany, humorous, or very personal associations will help you remember.

Mind Maps

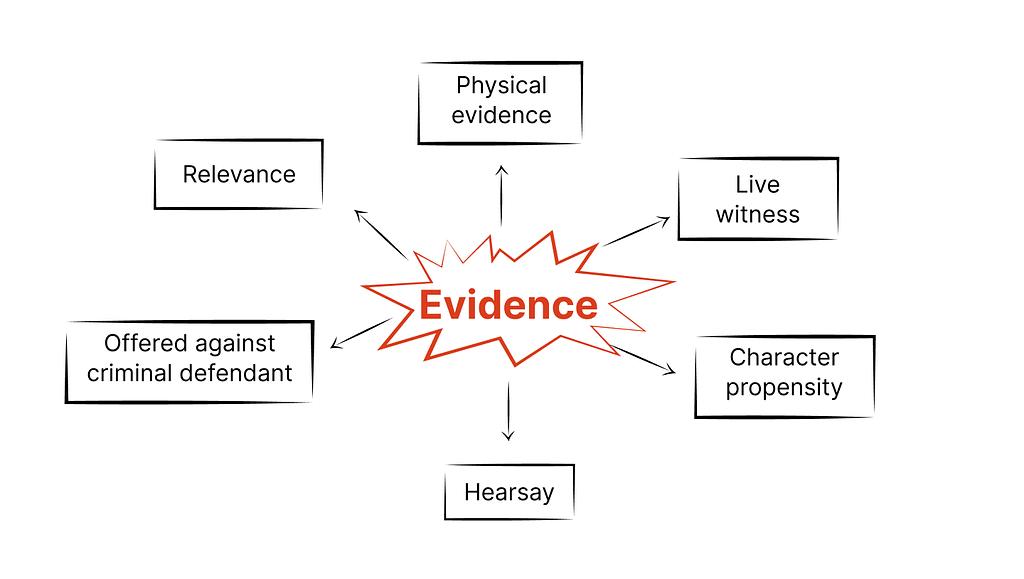

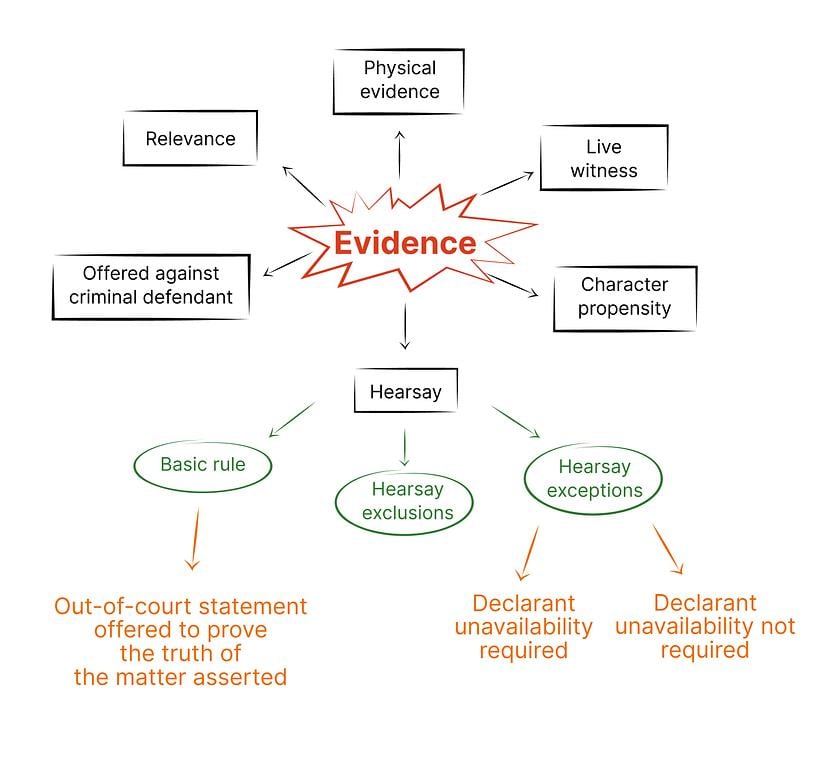

Mind maps are visual diagrams that cluster related concepts together. Start by putting the most basic idea in the center of a page, and then create branches using the major subtopics. From the subtopics, continue clustering information outward toward the margins of the page.

For example, evidence branches into several major subtopics, including relevance, physical evidence, live witnesses, character propensity, hearsay, and evidence offered against a criminal defendant.

Continue branching from the major subtopics. For example, hearsay can be broken into the basic rule or definition, exclusions from hearsay, and hearsay exceptions. Continue adding detail to the map, clustering related concepts together.

When you’re at the point of listing rules beneath topics, be selective about what you write. Write the core standards you want to remember.

Mind maps organize information in related clusters, echoing how your brain encodes information. Mind maps also give you a framework to support learning. Bar prep requires learning not only the basic core of each subject but also exceptions and more obscure rules. You can assimilate the information faster and remember it better if you can fit this minutia into categories.

Mind maps continue to offer benefits during practice testing and on the bar exam itself. By mentally working through the areas of the map, you can spot the issues in a fact pattern and turn toward creating an organized discussion on an essay.

Tips on Memorizing for the Bar Exam

Memorization is a crucial element of success on the bar. Use these tips to get the most out of your memorization sessions:

- Start small, and prioritize what you memorize. It’s easy to get overwhelmed by the vast amount of law tested on the bar exam. Start with a small topic and consider using performance data from your bar course to inform your efforts. If the performance data shows you’re struggling with a topic, that’s a clue to spend time reviewing and memorizing.

- Distribute memorization practice. You’ll retain information better if you return to the same material during several study sessions spaced over time.

- Keep distractions at bay. Focused attention is a prerequisite for memorization. When you study, disable notifications from texts, email, and social media.

- Use breaks to refocus your attention. Scheduled breaks can help you accomplish more. Taking one 5–10 minute break for each hour you study is a good rule of thumb.

- Get adequate rest. If you’re sleep-deprived, you won’t have the focused attention required to shift information into long-term memory. Plus, sleep plays a vital role in consolidating memory.

.png)